WITH MORE THAN 550 ONE-OF-A-KIND HISTORIC BUILDINGS UNDER ITS JURISDICTION, THE U.S. GOVERNMENT IS A LOCATION SCOUT’S DREAM

While fighting city hall, as the adage goes, may hold plenty of challenges, filming in it—or a courthouse, post office or any number of government-owned locations—is a much more positive experience. That is when location scouts work with the GSA Center for Historic Buildings, a division of the Washington, D.C.-based U.S. General Services Administration. A byproduct of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the nationwide program was developed to encourage the use of the government’s historic buildings in film and television productions. Its goal is to showcase and support the legacy of these buildings by creating opportunities for the public to experience them through film. Additionally, all revenue earned is reinvested in the historic inventory. From the Louis Simon-designed 1936 IRS Building in Washington, D.C., and the majestic U.S. Custom House in New Orleans to some 500-plus buildings around the country, finding a unique film location is—more or less—there for the asking.

To get the details on the filming process in government buildings, Destination Film Guide spoke with two experts at the GSA Center for Historic Buildings: Film & Special Event Program Manager David Anthone, whose area of coverage includes New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands; and Historic Preservation and Fine Arts Specialist Victoria Clow, who oversees programs in Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas.

The Jacob K. Javits Federal Building and James L. Watson Court of International Trade in New York, New York

Talk about the early years of the program

David Anthone: When I began working here 20 years ago, I was seeing the film industry in New York City, which is one of the epicenters for filming, asking GSA for locations. Prior to my coming onboard, those were being fielded by the building managers. There wasn’t a formal process in place even though there was filming going on as far back as the 1940s. I began the process of tracking requests and licensing. Once we issue the license, that grants the film studio formal permission to be in our building for that time frame and move through the spaces as agreed. It provides protection on both sides.

How many buildings are part of the program?

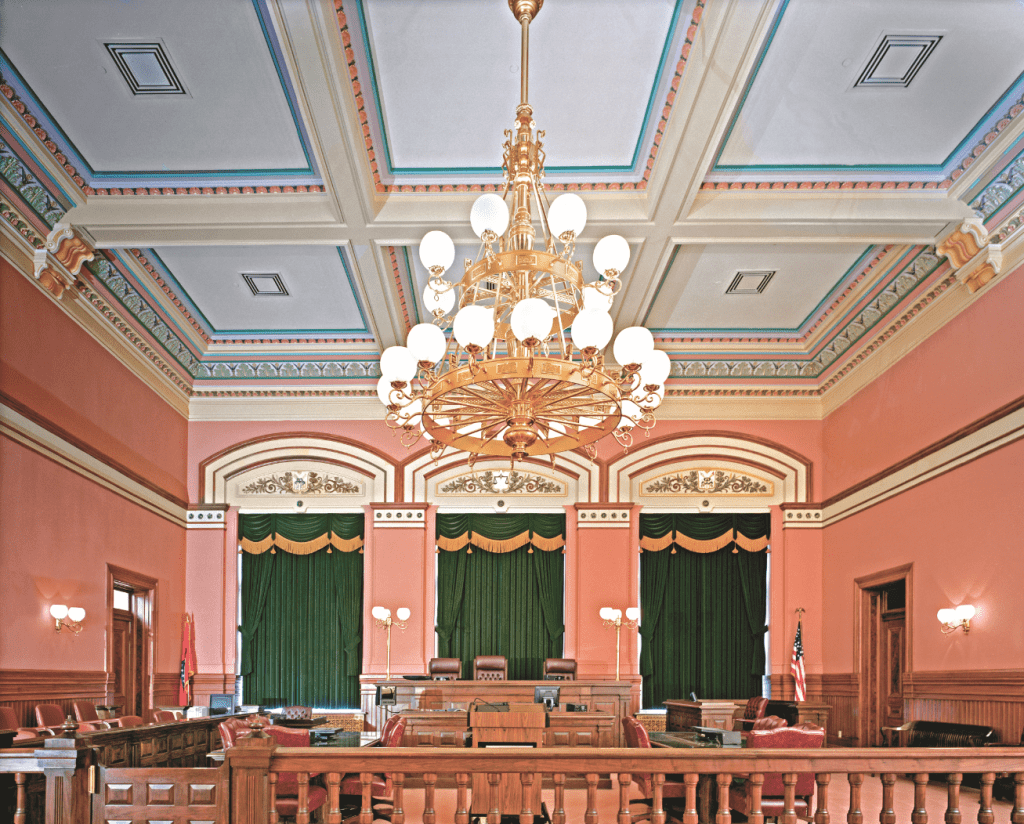

David: While there are 515 historic buildings in the program, not all are film-friendly. It fluctuates. Sometimes courthouses are considered not the most conducive for filming, but that’s not necessarily true. It is perhaps true for TV because they have union rules where they can only film Monday through Friday, which doesn’t work with the building’s schedule. But a big motion picture can film on the weekends, which is much more accommodating with the court schedule. In the condition of a courthouse, we would partner right away with the courts to get them on as an internal stakeholder to see if this schedule works for them. We handle not just historic but all buildings and properties. The industry doesn’t just want the pretty historic buildings; they want basements or lighthouses or fields. It can be anything.

What are some of the most popular ones?

Victoria: Our big film location is the U.S. Custom House in New Orleans, which has this impressive marble hall. It’s just gorgeous and it is very flexible as to how it can be adaptive to a variety of locations. We have vacant space in the building, which allows us to have availability for a green room, staging and layout. Even though it’s on Canal Street, we can accommodate quite a bit there versus some of our other locations where we are fully occupied. In general, we have fewer requests in my area. That largely depends on the film incentives in the state. Sometimes we get a lot of requests and then it goes down and that’s because tax incentives have sunsetted in that area. The income generated is important as it helps us maintain our historic properties and allows us to do projects we wouldn’t normally be able to do if it weren’t for the funds created through filming.

David: For me, it’s the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House [NYC], which historically could mimic the Met or even civic buildings in Washington. There’s been a shift because TV has changed, and they want to be truer to locations. There are a lot more crime and FBI and law shows and they want to film on location. In general, midcentury buildings are really picking up. Once they [location scouts] find the number of resources we have and the vast number of typologies available, they get excited. Even though they are coming to the building to do a site visit for one film, I can see in their eyes they are thinking about the potential of these spaces for future locations. Once a scout knows that a building is film-friendly, word gets out and it really catches on.

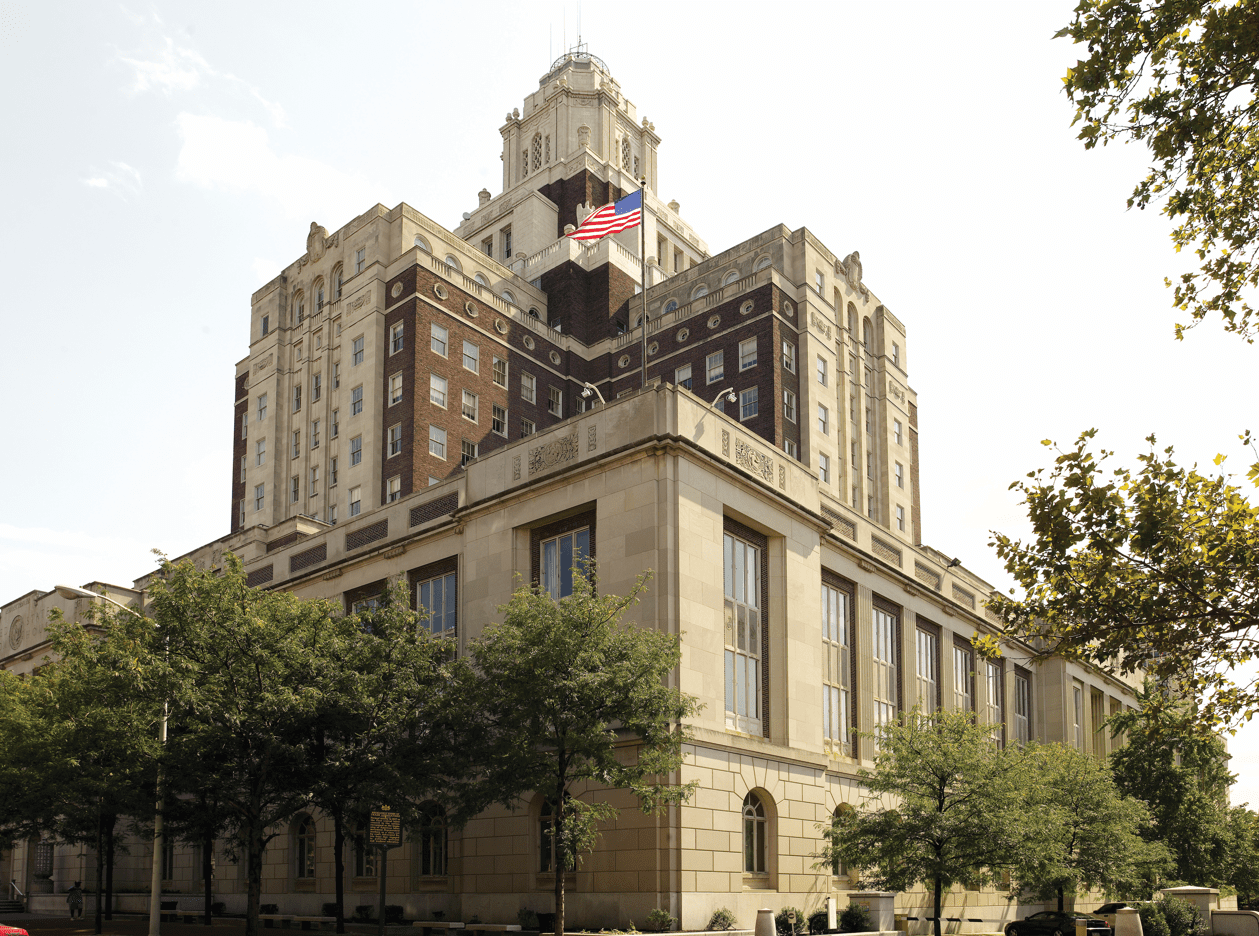

The Frank M. Johnson, Jr. Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, Montgomery, Alabama

How far ahead of filming would you recommend a proposal be submitted?

Victoria: In my region, we need quite a bit of time in advance because we do have to coordinate with our tenants. Also, we have to go through background checks with individuals coming on site. There are a lot of logistics. We are flexible, but if it’s 2 weeks and you want to be on our property that’s going to be hard for us to accomplish.

David: In New York, we don’t like a window that’s too far out because things change. We know it’s a moving target for films, so we want to be within a sweet spot of anywhere from 2 months to 10 days. We do have a rule in New York of 10 days minimum, but there are exceptions. We gotten that as short as doing a major motion picture license within 3 hours. That works in our region because the building and tenants are familiar and comfortable with the filming process. Also, we have building management escorts, so we don’t have to do the security clearance. There’s always a GSA presence during the entire film shoot.

Regarding the proposal process, what would make a production get turned down?

David: Scheduling conflict is a main one. The first thing we do after the site visit and the scout is interested is give them an application. Then we check the calendar. If it isn’t available, we ask if this is their only date or can they be flexible. For TV, if they wanted to film Monday through Friday, we would ask if we could work with them on hours. Maybe they could come in early before work hours or after. If that doesn’t work and they really want the building, we try to see if they can film on weekends or on a holiday when the federal workforce isn’t there. The only other reason I could see is a heightened security level on the building or covid or something outside our means that is preventing us from moving forward.

What are some of the common misconceptions about filming in a historic building?

David: That you can’t. We at GSA aren’t just there for federal agencies; we are there for the communities these buildings serve. This is an outreach program that generates revenues for historical preservation. But the other component is it works within our good neighbor/urban planning program. That program is to broaden the reach of these buildings so we can create a sense of pride and place because these buildings do belong to the communities. This program is a big morale booster for the federal employees. They love to watch something new and exciting and they love to see it on television.

The U.S. courthouse, Little Rock, Arkansas

Once the proposal is approved, what tips could you offer to make the day-to-day filming process run smoothly?

Victoria: It’s making sure what they want to accomplish in our historic buildings is compatible with the building. We must have protection to make sure they don’t ding up our elevators or damage our marble floors just like at any property. We are going to look at what they plan to do in the building and see if they can put down protection to ensure they don’t cause any damage.

David: Through the prep shoot, you work out the logistics. We don’t want to have pyrotechnics in Custom House, for example, and we’ve had requests. For me, it’s training the building managers to be flexible and accommodating to requests. Also, we understand that even though you could formerly go through sit-down meetings and come up with the logistics for the agenda, there will be troubleshooting that happens during the shoot. Having the right mindset to be able to field those questions that are not captured in the license, like maybe they want to change a scene or go longer or shorter or turn

the lights on or move a banner. That’s on my side making sure that the GSA staff can do that comfortably and can troubleshoot those requests. The studio has a license to be in the building, so they have a legal agreement. Our job is to work with them to make sure that goes smoothly. I’ve always found its very mutual and respectful between the industry and federal government. They want to do what they set out to do and shoot their film and they want to build a relationship with the federal government because they will want to come back. We both need to behave.

Victoria: Once our property managers become familiar with the process, it’s very positive for us. For example, our property manager at the New Orleans Custom House works with several scouts on a routine basis and loves it. We were able to accommodate a large AC enhancement project in the building and restore the windows because we had funds generated from the filming in the building.

Are there any film projects that wouldn’t be a good fit for a historic building?

David: No, not really. We did have an incident in a NYC building of a request that came a week or two afterward someone had lost their life in a security institution. They wanted to shoot a sniper scene, but it was too close to the real event.

Victoria: We had one request to repel off our building. We turned that down. Danger for them and the building.

David: We also must be careful when we are filming in a federal building during the week and comingling with the federal workforce. If it’s a show that involves law enforcement where they are wearing uniforms and have rubber guns, we have to be very good about notifying the workforce by posting in the elevators that a film shoot is going to be going on and that there are going to be people in uniform with rubber guns. We then must make sure we staffed it properly. If the federal workforce community is curious and wants to watch, that’s one thing. But if they’re not paying attention and didn’t get the memo and see something out of the corner of their eye that something tragic or accidental may happen… We must prevent that from happening.

If someone was on the fence about filming in a historic building, what would you say to them to convince them?

David: A good scout isn’t afraid to ask. I admire the scouts who push the limits and say, Have you ever filmed here? I will ask and go to bat for you and if the answer is no, we will look for another location. There’s a world of opportunities in the federal government. And not just GSA but the park service, veterans administrations and all kinds of federal agencies that own properties. We are just scratching the surface of the potential of this program to create revenue for historic buildings.

For more information, visit this website.

Photos courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Carol M. Highsmith

Download the latest issue of Destination Film here.